For decades projectors have had a "feature" to counter some kind of trapezoid issue, called keystone correction, or keystone adjustment, it will technically make a rectangle out of your trapezoid… so to speak. If you care at all about picture quality, don't use it. Here's why.

The problem with not being perpendicular

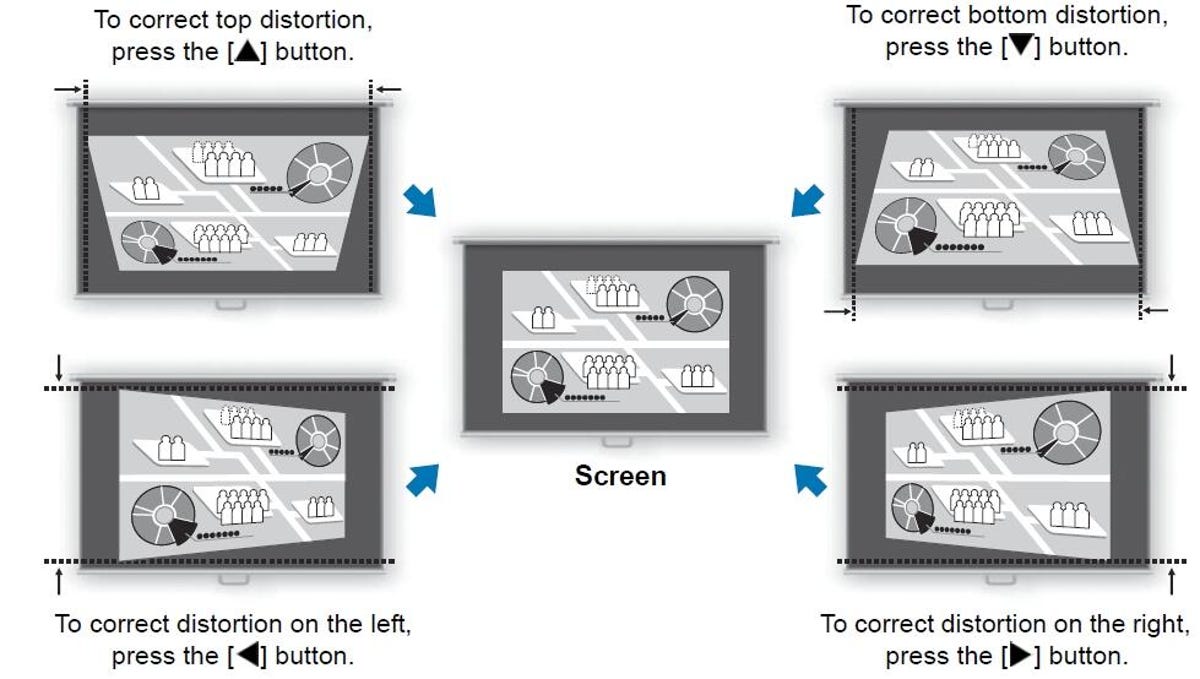

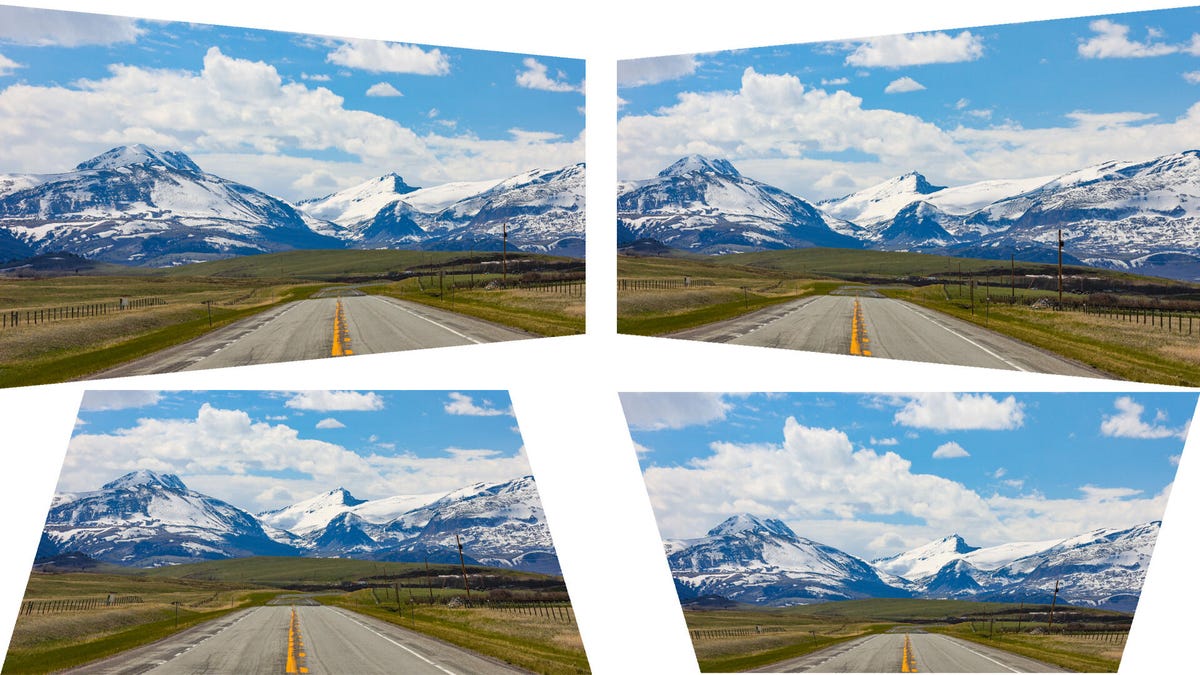

Examples of what your image might look like if your projector isn't exactly center. You would have to turn or tilt the projector to get it to line up, resulting in a trapezoid. Clockwise from top left: PJ too far right, too far left, too high, too low.

Projectors are a two-piece system: the projector and the screen. Even if you're using a wall or the side of your house instead of a screen, that still counts. All projectors use rectangular imaging chips to create an image, and it's crucial that the image sent by the chip is exactly perpendicular to the screen. Every corner needs to be the same distance to the screen as its opposite corner and if that doesn't happen, the shape gets distorted.Even if you've never used a projector, you've probably seen this effect in action. Ever used a flashlight? Point it directly at the wall and you've got a circle. Point it on the ground ahead of you, and it's an oval. Same concept.

Some projectors have a feature called lens shift, which mechanically adjusts how the imaging chips, lens and screen line up. Lens shift lets you move the image slightly on the wall without hurting image quality, but its adjustment range is limited. If you're beyond how far the lens shift can adjust, or the projector don't have lens shift at all, misplacement will cause the image to go askew.

Most screens have black borders so you don't need exact placement to the picometer, but it'd be a shame to spend money on a projector, and time on installing it, only to be annoyed at the visible edges when you're using it.

Which is why every projector has keystone correction. That doesn't mean it's good.

Keystone: Not even once

Keystone correction aims to solve electronically what is inherently an optical problem. The projector will digitally adjust the image in the opposite direction to offset the trapezoid. So if the image is, say, smaller on the left than the right, the projector can reduce the size of the right side so it appears rectangular again. Clever, right? Sort of. Unfortunately there ain't no such thing as a free lunch.

All modern projectors use one of three technologies, DLP, LCD, or LCOS. All of them have a fixed number of pixels, or picture elements, used to create an image. There's no way to change the number of pixels on one of these chips. These imaging chips are generally fixed in place as well.

What keystone correction does is scale the image smaller, and then further process it to form the shape required to "look" rectangular. Or to put it another way, it's drawing a trapezoid inside a rectangle, but because the projector and image itself is skewed, that trapezoid now looks rectangular.

Both of these things reduce image quality. Scaling, in this case, reduces the number of pixels used to create the image. You're only using a portion of the imaging chip to create the new image shape. The more you adjust the keystone, the fewer pixels are used, further softening the image.

Most projectors don't have much processing power, so this scaling might further soften the image, or it might introduce other noticeable artifacts. Changing the shape of the image is a further processing challenge and can add additional artifacts.

The principle of digital keystone correction is:

Pixel remapping: When the projected image is distorted by trapezoidal distortion, the image processing chip inside the projector receives a non-rectangular image signal. In order to "stretch" or "compress" it into a rectangle, the chip needs to resample and calculate the pixels of the image.

Non-proportional scaling: Imagine a trapezoid whose wide side is longer than the narrow side. During the correction process, the pixels on the wide side need to be "compressed" and the pixels on the narrow side may need to be "stretched" to make it a rectangle of equal width. This non-proportional pixel processing is the main reason for the poor image quality.

The solution? Place the projector properly

There's no better solution than not having the problem to begin with. Proper projector placement placates potential picture perils. Or to quote the ancient adage from prehistory: measure twice, cut once.

If you're mounting your projector permanently, double- and triple-check the mount is in the correct place for your projector. This is crucial. Most projectors, especially those based on DLP, have their lenses offset from the center of the projector. Ideally, your mount will have some adjustment "wiggle room," but it might not.

So yeah, if you absolutely have to use keystone correction, go for it. But it should only be used as a last resort in situations where you physically can't place the projector in its proper position. If you're mounting it, it's best to spend the time and get it right the first time and not rely on image-reducing electronic trickery to fix a bad install.

All of ByteSense's LCD projectors support automatic vertical keystone correction, and users can also perform manual 4-point keystone adjustment via the remote control in the settings. This keystone function is particularly useful when using the Gimbal series (G1/G2/G3/G3S) to project images onto walls (or screens) at different angles. Of course, the optimal viewing experience is achieved without using the keystone correction function—i.e., projecting images parallel to the wall—so that no image quality is lost.